FROM SUVLA TO MALPLAQUET

CHAPTER ONE

On the night of the 5th of August 1915 our H.Q. 34th brigade, 11th division embarked on His Majesty’s destroyer Bulldog’ (see figure below) and, together with the transports carrying the rest of the division, steamed from the island of Imbros towards the coast of Gallipoli. As we neared the Peninsula, the sergeants were busy issuing rum to the infantry, even going round for a second time to those that wanted it. Our brigadier explained to us that we would get our issue after the landing was made, as it was essential for us to be in full possession of our faculties as the lines of the infantry were dependent on the accuracy of our communications. So we RE Signals went into action dead sober, with no ‘Dutch Courage’ to help us. One other instance worth noting was the fact that Colonel Fishbourne of the 8th Northumberland Fusiliers was twice superficially wounded by ricochets from the funnel of the destroyer. A couple of days later he was again wounded and had to be evacuated to a hospital ship.

In the early hours of the morning of the 6th we arrived at our destination. We disembarked from the destroyer onto a K-type, shallow draught lighter, from which – after a time – we were transferred to whalers which headed landwards. Shortly afterwards we were ordered to get out, as the whalers were grounded 100 yards from the shore.

All of us were carrying our signalling equipment. I personally was carrying – in addition to my army equipment – two 4′ 6″ signalling flags, a quarter of a mile reel of cable, a D3 instrument and a heliograph and stand. On reaching the shore we were told to lie down on the sand and wait for the command to advance. At this time, the beaches were being shelled with shrapnel and we were also under fire from snipers further up the beach. We had no artillery to support our landing save that of His Majesty’s cruiser ‘Swiftsure’ (shown below, Wikipedia image) and one monitor.

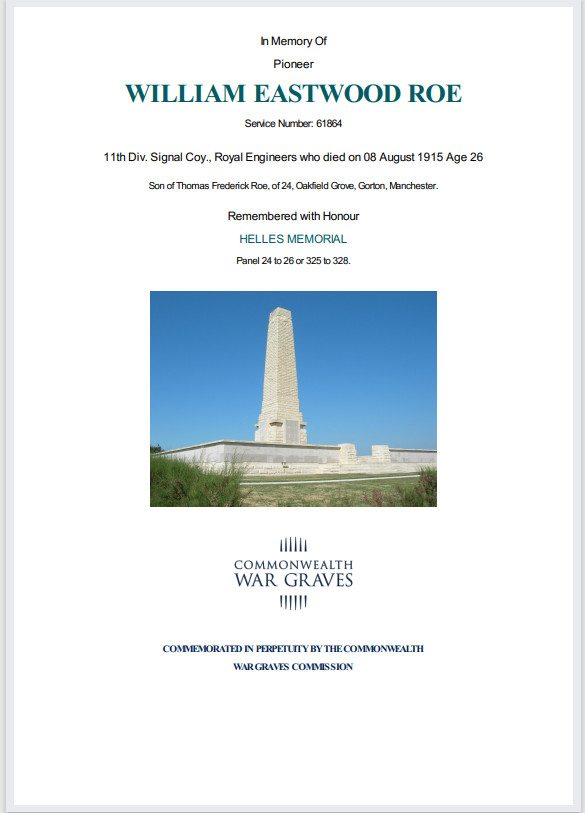

On the command to advance, we ran forward, some of us sinking into mud where water drained from the Salt Lake into the sea. Several of my comrades, hearing warning cries about the mud, went further along and crossed on dry land. We were then ordered to get down and take cover. Sapper W. Roe sat down with his back to a bush and Lance Corporal Eddy Ford at his feet. Suddenly, without a sound, Roe collapsed and it was not until dawn that we discovered that a sniper’s bullet had pierced his windpipe (see CWGC certificate). That same afternoon, Hickling (a close friend of mine) and I decided to bury Roe, because of the great heat of the day. We took his identification disk and the contents of his pockets and handed them to the Staff Captain. Bill Roe is commemorated at the Commonwealth War Graves Commission site, here.

One day soon afterwards, a Turkish envoy was spotted approaching our front line. This caused great excitement, as we all thought that they were going to surrender. No such luck, they were informing us that there was an ammunition dump near the hospital on the beach. They ordered us to move it or the hospital would be shelled. All available men, including most of us at Brigade HQ were ordered to move it, most of it being .303 ammunition for rifles. Bill Hickling and I worked together, finding an oar on the beach, we slipped it through the rope handles of the ammo boxes and carried them three at a time, supporting the oar on our shoulders. We had to move the ammo a distance of 400 yards and, by the time we were far enough away from the hospital, Johnny Turk shelled us with shrapnel to encourage us to get a move on. The results were a few casualties, but Bill and I did a bit of ducking down and thus escaped injury. By this time, our infantry battalions had reached the foot of the hills and were still advancing. We made our HQ on the beach and established communications with the other battalions of our brigade. Later that day, the battalions were held up on the hills, communications were lost and had to be re-established by runners. Towards dusk, myself and a private named Potter (of the ninth Lancs Fusiliers) were ordered to take priority messages, of which we both had a copy. The officer who issued the orders told us not to take our rifles, as without them we would get to the hills much more quickly. We were to contact each of our four battalions and deliver the messages to their adjutants. The first battalion that we contacted was the Ninth Lancs Fusiliers and by the time that we did so, it was dark. Eventually locating the adjutant, one Captain Guy, we gave him the message which he took and read by the light of his torch under the shelter of an overhanging rock. He had already been ordered to send a list of casualties to HQ, this message (telling him to do so) was therefore totally unnecessary and he told us in very strong language just what he thought of our signals officer, Beecroft, for sending us through dangerous territory on what had proved to be a totally pointless mission. When I told him that I had to deliver the same message to the three other battalions he advised me to go back to HQ and tell them that it was impossible to do so. I told him that we must at least try to deliver the despatch and he said “Right, I wish you luck”. However, after crossing the rough terrain for about half an hour I decided to turn back and make for the beach. The only guidance we had, were the lights of the hospital ships in the bay. A short time later we saw a silhouetted figure rise from the ground in front of us, I said to Potter “He doesn’t know that we are unarmed, so let’s challenge him”. This we did, and were greatly relieved to see him disappear. We then continued our journey towards the bay. After half an hour or so we were greatly cheered to be challenged in a broad Yorkshire dialect and I may say that I have never been so glad to hear an English voice as I was that night. We reached our HQ on the beach after an uneventful and tiring journey. When we arrived our Signal officer, Beecroft, threatened to put us under arrest for failing to deliver the despatches to the other battalions as we had been ordered.

CHAPTER TWO

August 7th 1915.The second day of the ‘Suvla Bay’ landing, General Mahon had taken ‘Chocolate Hill’ (see map) and I was sent with a congratulatory message from my brigadier. I had to make my way across ‘Salt Lake’ in order to reach the General’s HQ. On the far side of the lake, which was dry at that time of year, I saw some shallow trenches and in one of them I saw a Tommy in a kneeling position, with a rifle to his shoulder. I went up to him to investigate and found that he had been shot through the head. His head had fallen forwards and was resting on his rifle. He had retained his kneeling position and had not keeled over as one would have expected. Later, when I returned to HQ, I reported this and stretcher bearers were sent out to bring him in for burial.After this little incident I proceeded on my way and climbed to the top of ‘Chocolate Hill’ where I delivered the brigadier’s message to General Mahon’s HQ. I was about to start back when I heard a shot and turned to see an officer fall. It was a young lieutenant who was aide-de-camp to General Mahon. He had been shot through the lungs poor chap. Proceeding down the hill, I was confronted with a scene of real pathos.

Sitting with his back against a bush was one of our chaps, mortally wounded. I would say that he was about 45. He had a tobacco tin, pipe and matches and around him were spread several photographs of his wife and family He was having a last smoke with his thoughts on his dear ones as he died.

This depressed me considerably at the time and for quite a while afterwards. Later, back at HQ, I was in my trench and had just put the dixie on for a brew-up. While I was waiting, I went round to the next trench for a game of nap. I had not been away for many minutes when a shell burst right in my trench. When I went round to see what damage it had done, I found my dixie upset, the fire out and my despatch case blown about 40 yards. My game of cards had certainly saved my neck.Life here became static, as it was a question of digging in and holding on. I had been in the trench all day when Brigadier General Sitwell came along. He said “Signals have you got a rifle?”. I replied “Yes Sir”. “Can you use it?”. “Yes Sir”. “Then bring some ammunition and follow me”.

He said that we were going to the front line. He was a fine soldier and a good leader of men, and it was impossible for one to be afraid of anything in his company. Some time later we came to a well and stopped for a drink. The General spotted some biscuits lying on the ground. He picked them up, gave me a couple and said “Put them in your pocket, you may be glad of them by this evening”. As we approached the second line of trenches, the general noticed a man sitting on the ground, with another standing guard over him. The prisoner’s helmet was lying on the ground a few feet away. The general stopped, picked up the helmet and enquired as to what the man had been arrested for. A young officer in the trench said that the prisoner had been getting at the rum bottle. The only reply made by the general was to the effect that no officer had the right to allow the man to sit there with no helmet to protect him from the sun. A little later, when we arrived in the front line, the general picked up a clip of five bullets and, handing these to one youngster, said “Sonny, I want five Turks with these”. To another Tommy he said “Sonny, who’s your best friend? And for God’s sake don’t say your mother, it’s your rifle”. We spent several hours touring the front line and at the HQ of one battalion where the general stopped, he sent an orderly out with a drop of rum for me. I can assure you that I greatly admired him, he was a thoughtful, merry kind of man, as well as being a great soldier. A few days later, the general came for me again and a party of us proceeded to the front lines. The group consisted of General Sitwell, the brigade major, Captain MacIntosh the machine gun officer, his orderly and myself. We spent the whole day crawling through the old Turkish front line mapping out machine gun posts for an attack which was to take place on August 21st. Later on, while we were resting in a cornfield near an orchard which was being burnt in order to flush out some snipers, a corporal stretcher bearer came crawling in with a wounded man on his back. A chap named Sorano, of the Manchesters, remarked “By gum, that bloke’s worth a VC”. General Sitwell, thinking that I had made the remark, said to me “Young man you are quite wrong. We do not give VCs for doing one’s duty. I will see that he gets recommended. I wish to God that all men did their duty like him. You youngsters are not used to war, but you are all coming about quite nicely”. Corporal Gregory of the Manchester regiment was awarded the DCM, the next highest award to the VC. I sent the story of the event to the EVENING NEWS, and received a guinea for it when it was published. About the 16th of August I had an attack of dysentery, reported sick and was sent to hospital where I spent three days. I was then taken, with the other patients aboard a French hospital ship called ‘SALTA’. We then sailed to Mudros (see details) where we berthed alongside of the ‘EDINBURGH CASTLE’ (see details). It was rumoured that we were going back to England on it, but alas we only walked across it and the ‘GLOUCESTER CASTLE’ and down onto the shore. We were then taken to the Mudros harbour hospital which was on the island of Lemnos. the reason for our being removed from Suvla was to make way for the expected casualties from the attack on August the 21st. I believe that they were pretty heavy.

CHAPTER THREE

I remained in hospital for about a month and then passed as fit to go on convalescence. The convalescent camp was situated in the hills, near the little town of Portianos. About a week later I woke up with terrific pains in my head and shivering all over. The MO was sent for and he ordered that I be put in the hospital at the camp itself. While I was in hospital, I was told that I had had a mild attack of malaria, but at the top of my progress sheet were the letters FUO, which I later discovered to mean ‘Fever of Unknown Origin’. When I was finally released from hospital I had been ready to go for weeks but I had been kept there far longer than I thought was necessary. I count myself very fortunate that I had a good doctor, a man named MacRae. I had almost formed a mistaken opinion of him resulting from the way in which I saw him deal with a young chap in the Manchester Infantry. this fellow had complained of aching shoulders and arms, but MacRae had no sympathy with him, as he was of the opinion that the chap was a ‘malingerer’. However, when this fellow was examined by the other doctors, they could find nothing wrong with him and I realised that MacRae was not such a bad chap after all. MacRae examined me and said that, although I was no longer ill I was, in his opinion, still to weak to go back into active service. I said that I would rather return to the Peninsula and be with my friends, and so the following day I caught a transport back to Suvla Bay.

CHAPTER FOUR

I arrived back at the Peninsula that evening and, reporting to the BDE Brigade HQ, Ninth Corps Gulley, I rejoined my old unit and my friends. Although I eventually resumed my old duties, I was at that time supernumerary and, as such, was assigned OC Sanitation. I was able to go and pick out any four men and to take them round to empty the latrines. Whenever we passed the Signals Office the occupants would yell out “Look out, here comes Hillen and his shit carriers”.

I had this job for about six weeks until the Peninsula was evacuated, when I joined my unit in Egypt. Before I tell of my time in Egypt, however, there was another little incident that occurred while I was in Ninth Corps Gulley and which I shall never forget. We used to play brag all night and for illumination we used two cigarette tins of oil with a rope stuck through as a wick. In the morning, when we crawled out of our tent we met the divisional Padre taking an early morning stroll. Upon seeing us he burst into laughter and said “I never thought I should see the Moore and Burgess Minstrels here this morning”. When I asked him what he meant by it he said “Why, look at your faces”. Upon doing so, we discovered that our faces had become blackened by the smuts from the burning rope-wick that we had used the night before.Shortly after this, there was a terrible storm. Men’s bodies were being washed down the line and the storm did not clear until the following day. Sentries who had died in the fury of the storm were found dead at their posts. The storm was said to have been the worst since the days of Crimea. A man named Baily and I came off duty and a sapper named Davidson went on. This Davidson had bailed his trench out and had hung his things out to dry. As our trench was flooded too, we cut two channels and drained the water away. When Davidson came off duty he dropped straight into his trench, landing in two feet of water. The water which we had drained from our trench had run down the slope and straight into Davidson’s trench which was situated immediately below us. Davidson was furious and called Baily and I every insulting name under the sun, throwing in a few expletives in choice places. However, we thoroughly deserved it.Shortly afterwards, Lord Kitchener came to Gallipoli. During his stay he had a meal at our Brigade HQ. Afterwards, an officer told us that we were going to evacuate the Peninsula. Dumps were erected and boards put up and when the transports arrived to take us off, we were told that we could take anything from the dumps provided that we did not disturb them. My pal Bill Hickling took a whole side of bacon. I was less ambitious and took a tin of Irish butter. One of the first things that we did when we got aboard the transports was to go to the Galley for a drink, from there we were directed to the butcher. Another pal of mine, Robby, went to see this butcher. When we got there, he offered us two Guinnesses and when I gave him 10 shillings he said “That’ll be right”. Robby asked me if I would like another and my reply was “If I can pay 10 shillings, so can you!”. We arrived in Alexandria and took a lorry to Sidi Bishr, a suburb of Alexandria about four miles from the town centre. The Scottish Yeomanry had a bar there, but it was for members of the regiment only. We succeeded in getting a drink by borrowing six Scottish Yeomanry regimental badges. We were on the other side of a railway line to Alexandria and next to an oasis which consisted of about half a dozen trees and plenty of lizards. We were only here for two or three days before the entire regiment was moved to El Fedan, between Kantara and Ismalia. There was a fumigating train brought along and we were ordered to strip and place our clothes in this train. Meanwhile we had a swim in the canal or amused ourselves in any way that we could. When we had our clothes handed back and were putting them on, somebody said to Georgie Hull, a cockney in our brigade, “Well Georgie, how do you feel now?”. Shrugging himself into his tunic, Georgie replied “Blimey, I don’t half miss ’em!”. While we were here, we had a ‘very difficult’ job to do. Mine consisted of one night of duty in the Signals Office, after which I had 24 hours rest. I was able to spend this rest period as I wished. I was then given the job of counting the ships that used the canal, as well as getting their registration numbers and their ports. I also had to check dhows, for which purpose I had to swim out to them. On one occasion, a big hospital ship was coming up the canal and my pal Robby was standing on the bank with no clothes on. In order to avoid being seen in his undressed condition by those on board the ship, he walked into the canal until the water was up to his neck. However, when the ship had gone past the water level went down and poor Robby was left with the water round his knees, still waving to the nurses.

When we moved, it was to go further into the desert to a place called Ferryport, which was in the Sinai desert, about five or six miles from Suez. One particular incident, the memory of which has remained vividly in my mind ever since, occurred when we were riding out about eight miles into the desert with the Hertfordshire Yeomanry. We took a heliograph and a telescope with the job of warning them if we saw anything coming. Bert Miles spotted a large body of horsemen several miles off and, as nobody was supposed to be in front of us, he thought that something was up. We helioed back to base. Our orders were to remain there until the horsemen got within telescope range and, if they were the enemy, to mount up and run for it. I was later told that this report of ours about the horsemen caused great excitement when it was received back at base. As the body of horsemen neared us, we were told to tighten our horses’ girths and to get ready. The suspense of the moment was nerve wracking but, fortunately for us, they turned out to be the Australian Light Horse and not the enemy that we had dreaded. We helioed the news back to base and were told that the Aussies had no right to be there, this event caused near chaos in the official records for the area. After that, we carried on with normal duties and nothing of real importance occurred until several weeks later when we were told that we were going to France.

CHAPTER FIVE

Preparations were made to go to Alexandria and then we set off. From Alexandria we went on board the Cunard liner ‘TRANSYLVANIA’, a vessel of about 24,000 tons. Eventually, after about a week, we arrived at Marseilles from where we marched the two miles to Furneaux camp. We only remained here for a couple of days, however. When we left here, we entrained and proceeded to the battle area, stopping at intervals during the journey to eat meals prepared for us. After about four days, we arrived at St Paul. From here we went to Grand Roullicourt, where we stayed at the chateau for a week to ten days. The brigadier, J. Hill, had a sheepdog with him and he thought that it looked rather sickly so he said to Wiltshaw (the cook) “This dog looks ill, so here’s a bottle of brandy and a dozen eggs”. The eggs made Wiltshaw happy, and I felt rather merry as Wiltshaw shared his bottle of brandy with me. The dog, however, got better – even though he had not had the eggs and brandy and so the brigadier was pleased, as were Wiltshaw and I. One night we woke up to the sound of heavy artillery in the distance and received orders that we were to proceed up the line. We moved off the next day and went to a place about five miles behind the lines and stayed at the chateau at Beaumetz (see photograph below).

I volunteered to ride to Grand Roullicourt to pay the mayor of that town the money that we owed him for the billets. Coming across a couple of ASC chaps on horses, I asked them their division and they replied that it was the fourteenth. I then asked them if they knew a Regimental Sergeant-Major Hillen (my elder brother). One of them said that he was his groom and was exercising his horses. They showed me the direction of their camp and I called in on my way back. We had a few drinks and he agreed to ride back with me to Beaumetz. I did not stay at Beaumetz for long, as the Division went on manoeuvres and training. After about a fortnight, we moved to Bouzencourt where we were held in reserve for the attack to come on July 1st. We were about four kilometres from Albert, we never entered the battle but were held in reserve throughout. From here, we moved to another small village called Riviere, where we stayed in yet another chateau. We were quartered in the potting sheds and in the gardener’s quarters. This sector was fairly quiet as regards fighting. On our first morning in the line Jerry put up a notice which read ‘WELCOME 11th DIVISION, DO YOU LIKE THIS BETTER THAN SUVLA?’. HQ decided that, as they knew who we were, we had better find out who they were. Captain Armstrong of the 11th Northumberland Fusiliers was ordered to make a raid that night. He was ordered to capture one of the enemy and to use cold steel if he met any resistance from others (in order to prevent a flare-up). They came back with a Bavarian who, unfortunately, had been bayonetted during the mission and who died at HQ that same night. We were here until August. We used to have our meals in an orchard and one afternoon, when we were scrumping apples, we heard footsteps approaching from the back gate of the chateau. Everybody, with the exception of myself, took cover. I did not, because I thought that it would look odd if there were apples and branches strewn all over the orchard and nobody in sight. So, to prevent the officers from investigating the matter later, I decided to take the blame. I stood in the door of the greenhouse and waited until a few moments later some officers entered through the gate. They were the brigadier, the brigade major and a staff captain. The brigade major looked at the apples and branches strewn all over the ground and then at me and said “Signals, I hope they give you stomach ache”. The little group then proceeded on into the chateau. I discovered a little estaminet where I could get some champagne at only 3.90 francs per bottle. Robby and I bought a dozen bottles. One evening we were smoking and drinking when Lieutenant Barfoot came along and said “What are you drinking Hillen?”. I replied that it was champagne, and asked him if he would like to try some. He had some out of our enamel mug, rated it as good and asked me where I had got it and for how much. I told him and later, when I went to replenish my stock, I found that he had bought every bottle in the place for the officer’s mess. Some months later I met him in an estaminet in St Omer where I spoke to him saying “That was a nice trick that you played on us sir”. He said “What was that Hillen?”. I replied “Why, clearing all the champagne for the officer’s mess”. He said, “Never mind, have a bottle with me now”. So he shared a bottle with Robby and myself which cost him 19.70 francs, and this mollified me somewhat. About the end of August, we moved to La Baiselle – a fairly quiet spot. Our HQ was not far from where a brigade of artillery were quartered and where 4.5 inch howitzers and field guns were practically wheel to wheel. We had never been so close to such a heavy concentration of guns before and where the chief hazard was from premature bursts as some of the shells exploded on leaving the muzzle, causing quite a few casualties amongst the troops. I later heard there was quite an outcry in the papers at home. Questions were even asked in Parliament about the faulty shells that were sent out to us. As it rained heavily during the ten days or so that we were here, the ground was a quagmire and conditions were very uncomfortable. Eventually we were ordered to move to Orillers. When we lined up to get away, the QMS said that blankets were to be carried as the half a dozen cycles we had would have to go on the wagons. I suggested that myself and five others ride the cycles, with our blankets and kit bags going on the wagons. The QMS agreed to this, so we volunteers started off and had to push the bikes across a couple of muddy fields to the main road, and here our troubles started. The mud and slush were terrible, and it was as much as we could do to ride fifty yards and then stop and clean our mudguards and brake lights before being able to ride again. This went on for about an hour during which time I and my pals were alternately praying, cursing and crying, being thoroughly exhausted. I halted them for a rest, when presently I saw an ASC convoy of double limbers coming. I told them to get ready and, as each limber got close enough, to follow me and throw their bikes on and get on as well. I was the first to do so and the drivers, after first protesting, agreed to give us a lift to the main Albert-Bapaume road. I can assure you that we were very thankful for the lift. On reaching the road, we were able to cycle again. Bill Tobin, a runner from the Manchester regiment, said he believed that there was a canteen somewhere ahead. The others had no money, but fortunately I had. I promised them tea and something to eat when we reached it. when we eventually reached the canteen (a large hut at the side of the road), we found that it was a Canadian YMCA, so we got our tea and a snack for nothing. We were lucky in that at least.Eventually, we reached Ovillers and found our HQ in an old German hospital which was built – in a trench – on girders and massive timbers, and which was heavily sandbagged. There were bunks for us all. My pal, Ken Williamson, had promised to claim a bed for me and put my kit bag and gear on it. When he showed me the bunk, I found that a shell had landed on the top and had bent the girder so that I would have been unable to turn over. After I had roundly cursed him and called him every conceivable kind of pal for doing this to me, Ken just laughed. He then lead me to another bunk – he had only done it to hear me blackguard him. After a couple of hours sleep, I felt much better and ready to go on duty in the Signals Office at midnight, with Robbie and Ken Williamson (who was the divisional Sounder Operator) and half a dozen runners. Robbie, who always did a lot of scrounging when we arrived at a new place, told me that he had found a nice white enamel jug fitted with a cup as a lid. This would be OK for our brew-up later, when we got our Primus spirit stove working. I must tell you that we were provided with several petrol cans of water plus another couple of cans with the corners cut out – to urinate in. In the early hours of the morning I suggested to Robbie that it was time for our brew-up, so he proceeded to fill one jug with water and to get our Primus stove going. After some minutes, we noticed a pungent smell which steadily got worse. Going to the stove, we took off the lid, took one more sniff, and hurried to the trench where we threw the jug and contents over the top. Some of the previous occupants had urinated in used some of the ordinary petrol cans and that was what we had been boiling up. We then had to fill our service canteens and make a fresh brew-up of tea.

SEPTEMBER 1917.

After a day or so, preparations were made for an attack at Theipval. It was aimed at the German front line and, more particularly, at the redoubts and strongholds of Hohenzollern and Schwauben, which had been causing a lot of casualties. It was a fine morning when the barrage went up and as soon as the infantry moved forward we got a surprise for, following the infantry, were tanks. Myself and a couple of pals, not being on duty in the Signals Office, came up from our dugout to have a look at them. They looked very clumsy to us with their bundles of branches and brushwood on top. These were for dropping into trenches in the tanks’ path, thus filling them in and allowing the tanks to pass safely over. These tanks succeeded in putting the wind up Jerry and we quickly advanced. This advance was only temporary however for when one of these tanks got stuck in Theipval cemetery the Jerries knocked it and several others out by using field pieces at what was virtually point blank range.

Also, there were not enough tanks to keep up the pressure on the enemy when they had recovered from the initial shock. I forget the exact number of tanks used, but I believe that it was between 7 and 11. I believe the former was correct. Meanwhile, the attack was going pretty well, especially with regard to our infantry and machine gunners, but the two redoubts were causing quite a lot of trouble. Both of them being taken and retaken by Jerry. We finally drove them out, and the officers chiefly responsible for this gallant action were Captain Archibald White (who was eventually awarded the VC) and Lance Corporal Spud Murphy of the 11th Manchester regiment, who fought gallantly in capturing Hohenzollern and Schwauben, was awarded the DCM. The above officer was the Yorkshire cricket skipper.After a few days, the attack petered out. We were eventually relieved and sent back to Morche, a village just outside Albert. Here we took over the billets of an Indian brigade and were housed in an old barn. After claiming my own portion of the chicken netting that was spread right across the barn, I went over to the Signals Office (a coal shed) where I was Signal Master. I was due to be relieved by Robby after midnight. At about 11 o’clock, I was much surprised to see Robby arriving an hour early to relieve me. I arrived at the barn and opened the door. As I did so, I heard the scurrying of many small feet and, in the light of my torch, saw a great many rats. They seemed to be everywhere. Anyway, I made my way to my bed and gratefully dived underneath my two blankets, where I stayed for the duration of a most unpleasant night. By some miracle, however, I did manage to get some sleep. The next day we marched to Villers, and this time got decent billets. All that we did for the next couple of weeks were a few mock attacks with the infantry. Time passed very pleasantly, we played a few games of football which we thoroughly enjoyed. Another activity which we revelled in was popping along to the estaminet to enjoy a few bottles of ‘Vin Blanc’ and ‘Graves’, which is a much better wine than Vin Ordinaire. A unique aspect of this estaminet was that it was owned by a sergeant of the Signals, who had married the owner, the widow of a French soldier. This sergeant was stationed locally and had what was virtually a permanent job at Corps HQ, so in his off-duty spells he ran the estaminet. He turned out to be a pal of Dixons who came from Leeds PO. Between us we managed to get quite a bit of fun, music and drinks and so you may well imagine our sorrow when we heard the news that we were going up to the front line again. Our division, the 11th, was to move up to Arras. This was now October, and Bill, Robbie and I were informed that our Blighty leave was coming through at any time. After three of four days of marching through the rain and slush, and sleeping in damp billets I managed to get a shocking cold. At the end of all this, I crawled into my bed feeling pretty queer. When Robbie and Bill came in and said that we had got to leave and were to catch a train from Railhead at Avesne Le Compte at about 06.30 in the morning. I felt so damned bad that I told them that I could not make it and would have to report sick. But they told me that I ‘was not bloody well going to do anything of the sort’. Robbie gave me a couple of quinine powders and poured half of the rum that he had been saving down me. He then told me to go to sleep and that they would wake me in time to catch the train. This they did, and not only carried my kit and gear but also took turns in helping me along too. Eventually, they got me to Avesne le Compse and onto the train for Boulogne. I considered their actions a splendid example of the camaraderie which existed between our boys. I am sure that there were very many such others. I often remember Bill and Robbie gratefully in my thoughts of the past.

CHAPTER SIX

We sailed from Boulogne to Dover, from where we took a train to Waterloo, Lewisham and home. Then, after 18 months, it gave me a wonderful feeling to be reunited with my wife and two babies. Ten days leave, what a lovely feeling it was to be home once again. A comfortable bed to lie in, regular meals and my family. Also visits to relatives and friends. I suggested to my wife that we should go up to town to see ‘The Old Bill’ (or perhaps ‘The Better Ole’), a comedy on the war by Bruce Bairnsfather (Captain Bruce Bairnsfather, a WWI soldier, began drawing cartoons in the trenches, capturing the everyday life of soldiers. His work, which resonated with both troops and the British public, led to regular features in “The Bystander” magazine, making him a renowned cartoonist. In 1917, he co-wrote “The Better ‘Ole,” a play based on his cartoons, starring his famous character Old Bill.), based on his famous cartoons of some Cockney characters. This was on at the Oxford, a West-End theatre in Oxford Street. It was quite funny, and we enjoyed once again going to a show together. On coming out of the Oxford, we made our way to the Empire in Euston Road. I had promised to deliver a letter from George Bailley to his wife, who was in the box office. After doing so, we then made our way to the Kings Cross underground station and booked to the Borough station. After going through a couple of stations, I noticed excited crowds hurrying onto the platforms. People of all ages, including women and children. Some of the passengers that got on informed us that an air raid was on. Our train was stopped at Borough station and we were informed that no-one was allowed into the streets as to be there was far too dangerous. The scene on the platform was quite interesting, women were fainting and kiddies who were not feeling too good were crying. Helpers were handing out water. I was sorry that it was nothing stronger. As the platforms were, I should say, about 80 to 100 feet below street level we heard nothing of the bombing. A chap coming down said that it was a terrific barrage we were putting up, so I said to my wife that I was going up to see what it was like. As the lifts were not working, I had to climb the spiral staircase which wound its way to the top of the lift-shaft. When I got to the booking hall, the gates to the street were closed and the police would not let anyone go out. As for the ‘terrific barrage’ I should think that there were anything from six to a dozen AA guns firing intermittently. And that’s what they called a ‘barrage’. When you are in an attack, the barrage causes the very earth and the air to tremble and vibrate. And to think that the Evening News started a Barrage Fund and called for donations to buy extras for the AA boys and make things more comfortable for them. Well, to continue my report of our trip out, after about an hour spent on the platform we were allowed to proceed on our way home. We found that we could only get a train as far as the Marquis of Granby at New Cross and no trams were yet running to Lewisham. So we set off to walk it, a journey of a mile and a half or so. By the time we got to St John’s station, the AA started firing again from Hilly Fields and shrapnel started falling. The wife wanted to run as we were both anxious about our two girls, who we had left in the care of their Grandma (the wife’s mother). I told her not to run but, if she wished, we could shelter in the doorways of some of the big houses on Loampit Hill, as they had pretty big porches and would afford quite good shelter. But no, she wanted to hurry and get back to the babies, which we eventually did, and found them quite safe with their Grandma. I don’t think I should have felt quite so peaceful in my mind if I had known that a bomb had been dropped on Dr Holt’s house, which was in a road which ran directly above us and which looked straight down onto Algernon Rd, where we lived. Dr Holt’s nerves were badly shattered and I believe he never practised again. One thing that impressed me on this, my first leave, was the kindness and trouble one’s relatives and friends took to do many things to make your homecoming a happy one. The wife’s elder brother bought a new gramophone and some new records. One which I recall with appreciation was an orchestral record called ‘The Masterpiece of Creation’, it impressed me so much that it was with a feeling of nostalgia that I thought of it when I returned to France. After two or three days, the wife and I decided to take the kiddies down to Wheathampstead where my father and mother had a small country pub, the ‘Rose and Crown‘. It was nice to see them again, and it also gave them great pleasure to see us. My father was very proud that all his three sons were serving abroad in the army. This spirit of patriotism does not exist today, except in those of my generation, or earlier ones. It seems that quite a lot of the youth of today are not at all proud of being English. After a couple of days, we returned home and enjoyed the remainder of my leave in what was a quiet and restful period. One amusing incident is worth recording. One night there was an air raid, though only of a light nature. After getting to sleep, my wife woke me saying “Alan, there is a bomb rolling down the roof”. After convincing her that all was quite OK, we got to sleep again, with no further incidents to disturb us. The final day of my leave dawned, and fairly early that morning my pal Bill Hickling arrived to spend the last day with us. It passed very quickly and early that night we went to Waterloo station. The wife and one or two members of her family came with us. We were joined there by Robbie, who had come up from Cardiff, where his home was. The scene at Waterloo was not very pleasant. There were soldiers and sailors with girlfriends and wives, some singing and some crying for various reasons. Some because they were really sad and some because they were crying drunk. There were boards marked for various divisions and units, stating the platform number and time of departure. At last we all proceeded to the platform. Robbie, Bill and I found seats in a carriage, put our kit in, then got out to say goodbye. Having said my goodbyes to the wife, we got back into the carriage as the whistle went. The doors slammed and we were off.

CHAPTER SEVEN

In Southampton we embarked on a transport. Once on board, we found a place below where we could lie down and get a bit of sleep. When we awoke in the morning it was to find ourselves at Le Havre. Here we entrained for Rouen, where we were to spend the night.I had forgotten to mention that, when Hickling joined us, he was wearing a medal ribbon. It was pale blue and white, with some thin red stripes on it. I asked him what it was and he replied that it was the new ‘Gallipoli’ ribbon which was being sold at Nottingham. Well, that evening at Rouen, the three of us went to the YMCA to get something to eat and drink. Sitting at another table I spotted a grizzled old warrior of a QMS and he was wearing the same ribbon as Bill, so I went across to him and said “Excuse me Quarters, what is the ribbon you are wearing?”. He told me that it was the Egyptian ribbon of 1895. I am not quite sure of the exact years, but I pointed out to Bill that it looked a bit silly being worn by a young man of twenty. He then took it off, and so ended another amusing episode. It was then about November 1st or 2nd, and we found our brigade in the back area of Beaumont Hamel, on the river Ancre. The 63rd Laval division started to attack on the 13th of November and during five days fighting they and the 63rd ND took Beaumont Hamel and Beaucourt, both ruined villages. This sector had resisted all of our efforts since the July 1st attack. The Royal Laval division, after much confusion, made good headway in small bands of raiders, one of which was commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel B.C. Freyberg (see portrait below, executed by Peter McIntyre). Despite being wounded several times Lieutenant-Colonel Freyberg continued leading his men towards a formidable redoubt and through wire which had hardly been touched by our barrage. Freyberg’s battalion, which had pushed up the bank of the river for about two miles, had to wait twenty four hours until their own artillery had ceased firing in front of them, before taking this redoubt. Our division went in support and during this attack I was sent with a message to 63rd ND HQ congratulating them on their success. That morning I was lucky enough to arrive in their trenches in time to see Lieutenant-Colonel Freyberg returning from a night raid on Jerry. Freyberg and his men all had their faces and hands blacked to make them less likely to be seen. Now, to digress a little, here is some information about Freyberg himself. He was awarded the VC for his part in the battle. A New Zealander, he tried for a commission in our army but, for some unknown reason, was turned down. Later on, he stopped Winston Churchill in the street and asked him if he could help him. At that time, I believe, Winston was the OC of the 63rd Laval division, quartered around the Crystal Palace. Churchill was so taken by the appearance and keenness of this young blonde giant (he was about 6′ 2″ or 6′ 3″ I believe, and about 14 or 15 stone) and he got him a commission in the ‘Hood’ battalion of the 63rd division. They, like us were in Gallipoli, and Freyberg swam ashore at our landing at Suvla Bay, lighting the flares to mark our landing places. Freyberg was a brigadier at 26 years of age and finished the war as a major-general and a divisional commander. He went on to become Lord Freyberg VC, Governor General of New Zealand.

Two other items of interest I have just remembered, he was wounded fifteen or sixteen times and after the war he attempted to swim the Channel, but his wounds forced him to give up a few miles from Dover.One final comment on the Ancre offensive. Throughout, it had been misty and cold with a thin drizzle, and the mud around and in front of the Jerry trenches was almost impassable. In one spot, the road below ‘Engine Trench’ a rear limber [p.14] of an eighteen pounder had sunk, so that you walked over it. On the 17th and 18th there was a blizzard. The result of the Ancre action was that we had straightened out a German salient. We now took over the front line from the 63rd division and Jerry got a bit of revenge by shelling us heavily and often. This made life very uncomfortable for us, but fortunately when off duty we had some very nice dugouts (apart from the rats) about thirty to forty feet deep to relax in. After about ten days we were relieved by another division. This was two or three days before Christmas. On the way to a back area, at one point in the journey we marched beside the river Ancre and, to our surprise, saw several dead Scotties in their kilts lying under the water. They all looked well preserved due to the temperature of the water, which had about an inch of ice on top. They came to be there because the town overlooking the Ancre had a large reservoir and when the Germans were advancing in late 1914 the townsfolk blew up the reservoir hoping to drown a lot of Jerries or at least make things difficult for them. Unfortunately they also drowned a few of our Highlanders who were also caught in the flooding of Ancre Valley near Beaumont Hamel while they were retreating. I cannot vouch for the above, but that is what the local peasantry told us. I can confirm that the Scotties were lying under the water, looking very well preserved and extremely peaceful, as if they were just resting there.We were looking forward to Christmas as before we took over at Beaumont Hamel, Captain Ratcliffe (a professional baritone singer) had gone on leave to Blighty taking with him a German Pickelhauber (which is a brass helmet with a spike on top). Captain Ratcliffe told us that he intended to auction the helmet at a concert in which he was performing. There he was to sing a song written especially for him, called ‘Laddie in Khaki. When we arrived at our billets we were greeted with the news that Captain ‘R’ had raised fifty pounds for the Pickelhauber at the auction. He had offered the cash to give us a happy time at Christmas. He had bought us turkeys, Christmas puddings and also some bottled beer and other extras. This was for NCOs and other ranks at brigade HQ, about 40 or 50 in all. Of course, we also had our normal rations, including several issues of rum. The ‘do’ was held in an army hut, it was some party and a wonderful time we had, both as to Christmas dinner and a good old sing song afterwards. I believe that Captain Ratcliffe was the man who inaugurated the communal singing at FA Cup Finals. So ended 1916.

CHAPTER EIGHT

In the beginning of January 1917 we went back to Beaumont Hamel for another turn in the line. Whilst we were there, some of the top brass decided they wanted to know what the Bosche was doing, so they sent ‘B’ company of the 5th Dorsets on a raid. On the morning of the raid there was a very heavy mist, almost a fog. After some hesitation, our brigadiers decided that they should proceed with the raid. They had been gone quite a while when some desultory rifle fire was heard and then silence. We never heard what became of them. We could only suppose that they had walked right into Jerry and were either wiped out or taken prisoner. When you consider that there were some 160 men involved, it seems incredible that they could just disappear like that. We had some of the Dorset attached to us as runners and they told us that, weeks later, their relatives had heard nothing from those missing.Well, after doing our spell in the line, we returned to one of the villages behind the line for a rest period. As our Signals Officer went on leave, he was replaced by a Lt Morgan, from an artillery unit. Now, as was customary when we came out of the line, our unit of about twenty men had a little lay-in on the first morning. Evidently Lt Morgan did not agree with this and we awoke to hear our sergeant and one or two junior NCOs telling us to parade for the officer’s inspection in about ten minutes. Well, as you might guess, we had not cleaned our rifles and most of us were unshaven when we were ordered to fall in. Number one in our front rank was a cockney and was noted for his five o’clock shadow. Lt Morgan halted in front of him, saying “Did you shave, my man?”. The man replied “Yes sir”, in his broad cockney accent. Morgan then asked sarcastically “May I ask what with?”. “Yes sir, with an army razor”, and there was a general titter in the ranks. But Morgan, knowing that he was very unpopular at that moment decided to dismiss the parade and to cancel the afternoon parade also. The joke was that you hadn’t a hope, trying to shave with an army issue cut-throat razor.Eventually, the 34th brigade were withdrawn from our division to take part of a flying column. A Signals Office was fixed up in a big lorry. Our artillery’s 18-lb field pieces were also mounted in lorries, together with our brigade of infantry. The attack was to be the other side of Arras, the aim being to break through the Docourt Queat Switch. The cavalry were to lead the attack, with us in support. This entailed us moving back to Grand Roullicourt for over two month’s special training. While we found this pretty arduous, it was relieved by a couple of football matches each week (at the brigadier’s suggestion) with the other units attached to us. Lt Webb made me OC Sport. My job was to fix the matches and arrange for transport, a meal, a bath or shower for the visiting team wherever possible. This did not excuse me from training with the rest for the job we had in hand. We had a good many enjoyable games. I played right half for the brigade HQ team.I must tell you of one match against the machine gunners, whose team included three or four professional players from the north of England. Well, poor old Lee, our goalkeeper, was smothered in boils on his legs and thighs and had great difficulty in moving about. I am sorry to say the machine gunners fairly riddled our defence, to the tune of nine goals to one. Poor old Lee could not jump about enough to stop the many shots fired at him. One spectator suggested that if Lee just walked up and down his goal line some of the shots must hit him. A very logical, but unkind, remark. But do not think it all went like this for us, we had our share of victories also and we thoroughly enjoyed both our special training and the sport. We eventually moved up to Arras for the attack. When this took place, the divisions involved in the attack took their objectives but were held up and did not make the breakthrough that was expected. Therefore neither the cavalry, nor our flying column could be used. Accordingly, our divisional commander, Major-General Davies had our brigade returned to the division, so ended an enjoyable interlude for us. We next moved to Bapaume, which had just been captured by our army corps. We were quartered at Lorche, four or five kilometres the other side of Bapaume. This was nice, rural countryside and quite enjoyable now that the attack had died down. Our infantry were busy digging themselves in. We had four or five huts as Signal Office and sleeping quarters. In the same field was a 45 howitzer battery. While they were shelling Jerry one day, we witnessed a nasty accident with one of their guns. As the breech was closed there was a premature burst and the breech was forced open by the explosion. The terrific flames blew back on the gunners, seriously injuring the Battery Sergeant Major and several men.After our spell in the line, our division was withdrawn to a nice little town called Beauquesne, not many miles from the chateau which housed Field Marshall Haig. Our corps was to train for an attack up north, on the Belgian front. One amusing incident here was as follows. Outside our Signal Office (which was located in a school) there was a red lamp. To our amusement and their annoyance, two drunken men came in one night and played merry hell when they discovered that the red lamp did not signify what they had thought. A red light being the French sign for a brothel.Well we settled down to our usual duties and all but Sergeant Gwinnell were billeted in a huge barn in a field. This included Sergeant Giles, our three junior NCOs, the rest of us RE Signals plus the battalion runners who were attached to us. We were awakened one night by shouts and groans coming from one of our runners. This was Bill Harris of the Manchester Regiment, a veteran of the 29th division, who had come from India with them. Bill was delirious and obviously in great pain, a doctor was fetched and Bill was rushed off to hospital. In the morning we were informed that Bill had died in the night, from cerebra-spinal meningitis. The field company were busy putting barbed wire all round our field, and the remainder of us had to have our throats swabbed. We were all placed in quarantine for fourteen days, with a sentry posted outside to see that no-one got out. At this time there was a very bad epidemic of cerebra-spinal meningitis among the troops, and it was generally fatal. This caused a lot of worry to those in command. Our officer and Sergeant Gwinnell being the only two of the RE Signals available. They set about putting together a Signals Brigade Section from Signals from other battalions. They of course were not used to our ways and general procedure. Lt Webb didn’t want this, as we were expected to go into action in the next nine or ten days. Lt Webb chased everybody to try and get permission to take us with him when the brigade moved but up to the day before the division was to move off, he had not succeeded. We were issued with pay and rum and left to get what we wanted. We said goodbye to the sergeant and were generally quite happy. But Lt Webb, who was a real go-getter, was not finished. He got on a motor cycle and rode to Abbeville where the Deputy General Quartermaster of Signals was. He got to see him personally and suggested that as it would take five or six days marching to get to the area where the attack was to take place that, if we were allowed to march some miles behind the rest of division. We could bivouac in the open, away from the other units. In that way, before we reached our destination, we would all be out of quarantine. The Deputy General Quartermaster of Signals took the matter up with the top brass medical authorities. The latter granted Lt Webb permission to do just as he had suggested and he arrived back at Beauquesne just as our division began to march away. Lt Webb soon had us fallen in with our equipment and on the march at least one mile behind the last unit. A well-deserved victory for initiative and persistence.By the time we reached Baileul we were out of quarantine and back once again as 34th Brigade Signals. Lt Webb was quite happy. We now knew that we were for either Hill 60 or Mont Kemall. Marching on the way up there we saw the Flanders poppies growing amongst the scattered graves on the edge of a cornfield. These were the graves of some of the 1914 army and we were given to understand that they had been buried by civilians, although I cannot vouch for this. The area we were now in was only a few kilometres away from Poperinghe where the C of E padre, better known amongst the troops as Tubby Clayton, founded Talbot House. It was thereafter known as Toc H. It was well-known to all Tommies and is still in existence today, with branches all over the United Kingdom.On about June 4th 1917, we arrived at a place called Chinese Wall. There were no dugouts, only sandbagged sleeping areas. Our brigade was in support of several Irish battalions. Directly in front of our brigade was the Royal Irish Ulster Regiment, in the front line, over 1000 yards ahead of our infantry. At 3.10 am on the 7th of June 1917, the mines went up, taking the whole German front line and reserve trenches with them and leaving two craters roughly sixty feet deep and about sixty feet in diameter at the top. This was followed by a colossal barrage 700 yards deep which crashed down on the remaining defences.The following is a quote from ‘The First World War’ by Cyril Falls. ‘Some 2266 guns of all calibres were used by us. A divisional commander described the scene from Kemall Hill as a vision of hell. The noise of this battle and the explosions as the mines went up were distinctly heard in England’ (unquote).There was just one small incident while we were at Chinese wall. One nice, sunny afternoon, Bob Whitehorne suggested that we go for a swim in a large pond nearby. We quite enjoyed the first half an hour. Suddenly the sky got darker and it looked like a storm. Before we could get dressed, down came torrential rain. We scrambled out, putting our boots and clothes in some large tins that were there and turning them upside down to keep our things dry. We then dashed back into the pond, there being no shelter anywhere nearby. Then, to make it more enjoyable Jerry started sending over some Whizz Bangs and every time we heard one coming we would dive under the water and hope for the best. So what with the storm and shelling, the last half an hour spent there was quite an interesting experience. When the storm and he shelling eventually ceased, we got dressed and went back to Headquarters.After finishing our spell in the lines, we went back to a camp a few kilometres from Poperinghe. After about three weeks rest, and with the infantry brought up to strength with reinforcements, we began to prepare for the Third Battle of Ypres (First Phase). Our objective was the Steenbeck, which was not much more than a stream, with Jerry holding the other side. I was in charge of an old German pill-box, the entrance of which faced the German lines. The door was protected by a large block of reinforced concrete, the top 4 feet of which had been hit by one of our own 15″ inch shells, bending it double and leaving a gap at the top. The evidence of what had hit was still lying there. It was a dud, and had not exploded. The reason I mentioned the gap at the top was because I had to put my groundsheet up to prevent Jerry seeing the light from the 2-valve Uprive? [p.26] amplifiers which we were using at the time. At night, even a glimmer of light can be seen from quite a distance. The bombardment started on the 18th of July and carried on until the 30th. Just before the advance started on the 31st of July I had gone out with one of my chaps to check if my lines were OK. An RC padre named Clark was building a small shelter behind my pill-box just big enough to take about four stretcher cases. It was a lovely morning, with the sun just coming up as the creeping barrage started to cover the advancing infantry. I heard the padre shouting to me but I could not quite make out what he was saying. Thinking he was saying that he hoped the attack would be a success, I cupped my hands around my mouth and shouted back “I hope so sir”. At that, he started walking towards me, on reaching me he said “Signals, you’re a funny chap”, I said “Why sir?”, he replied “I shouted ‘I hope you won’t be my first casualty’ and you replied ‘I hope so sir’”. He had a keen sense of humour. I am sorry to say that the padre himself was killed later in the day. I was very sorry, for he was a really good man.

CHAPTER NINE

This attack, on the 31st of July was successful and some 3000 yards were gained, including the Ridge which gave us a view of the lines on quite a large front. This advance was known as the Battle of Pilckem Ridge. The attack itself only lasted three days, and was halted by a very rainy period. The remainder of our time was spent digging in, consolidating our gains and preparing for future operations.It was during this last action, and I believe the second night of the attack, that Sergeant Giles and Second Corporal Marden had been laying lines. After completing their task, they and the rest of their party took shelter in my pill-box, owing to the very heavy shelling. This made us a bit pushed for room. Sergeant Giles was sitting on a petrol can with Corporal Marden next to him. There were about 16 of us crowded into this small space, which was about 12′ by 12′. We tried to get a little sleep, leaving two men on the phones to take any messages that came through. Sometime during the early hours of the morning, a shell burst right outside our doorway and one or two pieces of shrapnel flew in, one hitting Marden behind his left ear. After bandaging him, we laid him on a stretcher and made him as comfortable as possible. It was a good twenty four hours before we were able to get him away, as Jerry had dropped a box barrage around us. Until that lifted we could not get him away. He seemed quite cheerful the morning he went. Some fellows were giving him letters to post and he gave away some of the things he did not want to take to hospital with him, including a ‘Webby’ revolver, which he gave to Sergeant Giles.We came out of the line that night and moved back to Siege camp. Next morning, when the despatch came for Brigade Headquarters, we learned that second corporal Marden had died from his wounds, in Proven Hospital. This was quite a shock as, to us, he had not looked like a dying man. He had been quite cheerful, shaking hands and wishing us luck. Some of us thought he might have been hit again while being carried down the line to a CCS. Anyhow, that was the end of poor old Dan Marden. After two or three weeks out of the line, preparations were made for the second phase (16 August 1917) of the Third Battle of Ypres. Our next action was the Battle of Langemarcke. This attack started on the 14th of August 1917 in terrible weather. Nothing but rain and thunder storms, while the barrages churned the ground into quite deep shell holes which were lip to lip and filled with water. Even the duckboards had been blown to pieces in places by the shellfire. There was nothing to do but keep plodding on and I and my party were jolly glad to reach our pill-box, which was an advance post just behind our infantry when they went over. Unlike the Somme, Ypres had no dugouts and no real trenches. There were only roughly thrown-up earthworks, slightly strengthened by sheep hurdles. The line was not continuous, in some places there was a hundred yard gap between here and there. The so-called ‘lines’ were held in parts, by a mere platoon of men. Our brigade was spread over a mile, with a few companies dug in as reserves, perhaps fifty or one hundred yards in the rear of the front line. There were miles of flat ground, and nothing to be seen but a few pill-boxes dotted around and one or two skeletons of woods. One notably called Kitchener’s Wood. When I took over the pill-box I had about 16 runners and about four of us RE Signals. We were responsible for lines forward to our battalions. They were the 11th Manchesters, 8th Northumberland Fusiliers, the 9th Lancashire Fusiliers and the 5th Dorset regiment. We were also responsible to Brigade Headquarters in the rear. The attack was successful, but it was a very bloody action, which halted after only three days owing to the conditions. The night before we were relieved, three officers of the Dorsets took shelter in my pill-box. They had been relieved and were on their way back. One Captain Knight was pretty upset as his servant (batman) had been blown to pieces in front of him, and his clothes were now stained with this man’s blood. Captain Knight, and all of them in fact, was overwrought, so I sent George Cresset out to get some water from a nearby shell hole so that we could have a brew up and give them a cup of tea. They had no smokes, but I was able to provide them with some for which they were very thankful. Having spent the night with us, Captain Knight said “Signals, have you soap and a towel we could borrow?”, I replied “Come with me sir, I am just going to have a wash”. So we went outside to a fairly bright morning and proceeded to have a wash. Captain Knight said “Signals, I hope your chap did not get water from this shell hole when he made the tea last night”, and pointed out that a man’s arm was moving about in the shell hole. I expect that our washing had disturbed some of the mud and left the arm showing. Later in the day we were relieved and returned once more to Siege camp near Poperinghe for a few days of rest. The next action was the battle of Polygon Wood from the 26th of September to the 3rd of October. This was followed by the Battle of Poelcapelle -Passchendale which started on the 9th of October. Once again, I was put in charge of a pill-box with about 16 battalion runners and responsible for the maintenance of lines and communications back to Brigade HQ and forward to all of our Battalion Headquarters. This was a pretty tough action, with plenty of casualties on both sides. About a couple of days before we were due to be relieved, Jerry’s shelling was particularly heavy and he got two direct hits on my pill-box with 5.9 shells. I mentally said goodbye to my wife and kiddies, as I thought that any moment now one will come in through the doorway (which faced Jerry’s lines) and with a blinding flash that will be our lot. But anyhow, it never happened. That evening my line back to Brigade was down and I got a priority message from our battalions stating that Jerry had got a direct hit on the pill-box which was 11th Manchester’s HQ. It was an 8″ armour-piercing shell, which killed the Manchester’s doctors and the padre. They were asking urgently for the artillery to shell a certain map reference. I had only two runners left with me and when I ordered them to take the message back to Brigade they said they couldn’t, as they had shell-shock, and they were shaking like a couple of jellyfish. I told them they had not got shell shock but only accentuated bloody wind-up, but as this was a priority message, I could not risk sending these runners so I said to George Cresset “You and I must go”. Fortunately I had got the rum from my chaps, so we both had nearly a Golf Flake tin full of rum before we went. Jerry was shelling like hell, but thanks to the rum we did not care a damn, running along the trench to the steps to get on top. I tripped, put out my hand to save myself and felt my hand all wet and sticky. Just then a Verry Light went up and I saw that my hand and arm were in a dead man’s body. I can assure you all the effects of the rum were wiped out and we ran as fast as we could over duckboards and shell holes towards Brigade HQ.

As we arrived, Bill Hickling, seeing the blood on my hand and arm said “What’s the matter kid. Have you been wounded?”. I told him that I had not and went in to the Signal Office and handed in my message from the front line asking for Artillery fire as they were under very heavy attack. A sergeant of the Lancs, who was a DCM, had pointed out to me some days earlier that if our line to Brigade was laid to our left, via ‘Villes Maison’ it would miss the heaviest point of the barrage. Remembering this, I told Lieutenant Sinclair that if he gave me half a dozen men with a ¼-mile drum of cable each, I would lay a new line one my way back to my pill-box. He was pleased with the idea and promptly gave me the six men and the cable to re-lay the line. Well, I started off all right but had not got far when Jerry opened up and fairly swept the ground with heavy shell fire. I could not face it, and called my men back into shelter. This happened twice more, and the fourth time when I started he remained comparatively quiet and the line was laid successfully, without any casualties. I was very sorry that I had jibbed and recalled the boys three times, as my sergeant told me Sinclair was going to recommend me for decoration. After what George and I had been through in the last hour or so I do not think, even had they offered me a VC, that I could have gone through that hail of shells again. I must add that this new line lasted for two days, and only went down the morning we were coming out of the line.This led to rather an amusing incident. Sappers McQuarrey and Creed were sent out to repair it. This done, McQuarrey was coming back at the double when he stopped and shouted at Creed who was calmly walking along behind him. Creed stopped and went back to the shell hole where they had done the repair, stooped, picked something up and came back. It turned out that Mac had left his pliers behind while repairing the line and had the nerve to shout to Creed to go back and get them for him. Even though Jerry was shelling quite a bit, Creed did so. I told Creed that I would not have done so, but that Mac would have had to get them himself. A very cool card was Creed.

CHAPTER TEN